- The pandemic has created a new “risk divide” between (a) face-to-face workers who bear disproportionate health risks (exposure to COVID-19) and economic risks (exposure to layoffs), and (b) remote workers who are better protected from those risks.

- Because Black and Hispanic workers are more likely to be employed in face-to-face jobs (due to systemic racism and other institutional forces), they are exposed to a double burden of heightened health and economic risk. This employment-based channel of unequal risk-sharing is one way in which the current crisis has exacerbated long-standing racial and ethnic inequalities.

- The emergence of a heightened risk divide between remote and face-to-face workers might also be expected to intensify inter-worker conflict. Contrary to this expectation, we find that very few face-to-face workers are expressing resentment, with the dominant sentiment instead being a stoic fortitude (“inward gaze”), an appreciation that others are also suffering (“downward gaze”), and a recognition that “we’re in this together” (“outward gaze”).

In most economic downturns, the overriding problem is that workers can’t get enough work, and policymakers accordingly worry about how to increase employment and to supplement income until employment is restored. The current crisis is distinctive because, unlike such standard downturns, it entails more than a simple reduction in employment. Although current job losses are of course profound and ongoing, the crisis is also changing how work is organized. The key change here: The new post-pandemic class structure is increasingly built around a divide between face-to-face and remote work that governs the extent and type of risks that workers bear. The purpose of this report is (a) to characterize the health and economic risks that these new class categories entail, (b) to describe recent changes in the racial, ethnic, and gender composition of the new class categories, and (c) to explore whether this change in the structure of work is leading to new types of inter-worker relations and conflict.

We begin our report by reviewing how journalists, scholars, and other commentators have characterized these new class categories and the new risks they imply. We consider, in particular, whether journalists and other commentators expect the stark “risk divide” between remote and face-to-face workers to bring about new class-based conflicts and tensions. In the United States, class-based conflict has long been tamped down, but the emergence of remote work during the crisis has exposed inequalities in risk-bearing that, as some commentators see it, may increase tensions between those on either side of the risk-bearing divide. Although it is very plausible that new tensions of this sort are emerging, other commentators have suggested that they’re likely to remain suppressed during the crisis because we’re expected to “come together” in moments of collective or shared threat.1

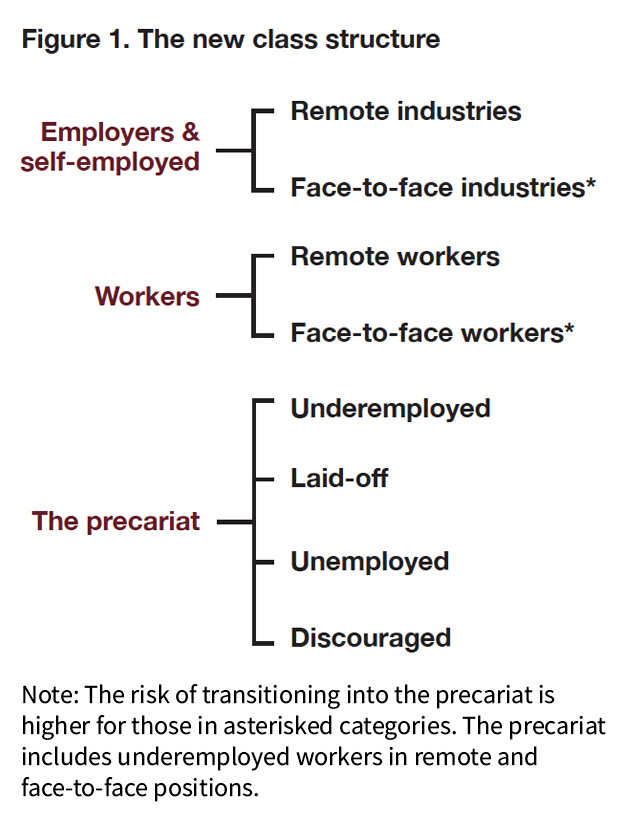

After reviewing recent commentary on the new risk divide, we will next provide quantitative evidence on this divide. In doing so, we will rely on the stylized class scheme shown in Figure 1, a scheme that emphasizes not just (a) the new divide between those who can work at home in relative safety (i.e., remote workers) and those who cannot (i.e., face-to-face workers), but also (b) the well-established—but now more salient—divide between those who face ongoing risks of unemployment or underemployment and those who are more protected from such economic risks. The striking feature of the new class structure is that face-to-face workers are disproportionately exposed to both types of risk (i.e., health and economic) captured by these two divides. Because face-to-face workers are, by definition, in close contact with customers and coworkers, they are disproportionately exposed to the health risk of infection and illness as well as the economic risk of pandemic-induced curtailment of face-to-face economic activity (via shelter-in-place orders, industry-specific shutdowns, maximum occupancy caps, and related reductions in customer flows because of concerns about infection). We will further show that this dual risk burden falls disproportionately on Black and Hispanic workers because they are more likely to work in face-to-face occupations (a type of “occupational segregation” that arises from unequal access to human capital, residential segregation, and other forms of systemic racism).2 Although there are many long-standing institutional sources of racial and ethnic inequalities in risk, the current crisis has strengthened the employment-based channel through which such inequalities are generated.3

The third section of our report, which relies on immersive interviews from the American Voices Project (AVP), addresses how workers from a wide range of communities in the United States are experiencing the risk divide and the inequalities it has generated.4 These interviews suggest that, while one might have expected unequal risk-bearing to generate resentment and conflict, instead there is much stoicism, fortitude, and even acceptance of existing class inequalities and the disproportionate risks they entail. For the most part, workers do not blame themselves for the problems they are facing, but neither are they typically blaming other classes. These are evidently problems to be borne in the way that, say, the British famously bore the trials of World War II. In one of our interviews, an older woman chastised those who complained too much about the pandemic, noting that “people get by, my parents had to go through world war and, you know, we’re not going through something like that.” The interviews that we’ll present will suggest, time and again, fortitude of precisely this sort.

The two stories in play

We begin by examining how journalists have represented the new risk divide and how scholars of risk might understand it. The two most prominent story lines in play describe a crisis that is either (a) supporting new forms of resentment and inter-class conflict (i.e., the “class conflict” story), or (b) calling into question the legitimacy of buying protection from health risks (i.e., the “buying safety” story). We review each of these two hypotheses in some detail because they have shaped the country’s current understanding of class relations during the crisis. After completing this review, we provide quantitative and qualitative evidence relevant to both hypotheses, the goal being to begin the task of examining how they fare against the data.

The American Voices Project (AVP) relies on immersive interviews to deliver a comprehensive portrait of life across the country. The interview protocol blends qualitative, survey, administrative, and experimental approaches to collecting data on such topics as family, living situations, community, health, emotional well-being, living costs, and income. The AVP is based on a nationally representative sample of hundreds of communities in the United States. Within each of these sites, a representative sample of addresses is selected. In March 2020, recruitment and interviewing began to be carried out remotely (instead of face-to-face), and questions were added on the pandemic, health and health care, race and systemic racism, employment and earnings, schooling and childcare, and new types of safety net usage (including new stimulus programs). The “Monitoring the Crisis” series uses AVP interviews conducted during recent months to provide timely reports on what’s happening throughout the country as the pandemic and recession play out. This report was sponsored by the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. To protect respondents’ anonymity, all quotations presented in this series are altered slightly by changing inconsequential details. Learn more about the American Voices Project and its methodology.

The “class conflict” story

The “class conflict” story rests on the hypothesis that many face-to-face workers see remote workers as retreating from the crisis rather than taking on their fair share of the risks. This formulation emphasizes the potential tensions and resentments between (a) remote workers who can protect themselves and their families by minimizing contact with the outside world and (b) face-to-face workers who have to bear risks by interacting with coworkers, customers, and the general public. In a recent Vox article, an Instacart shopper and freelance writer notes, “I buy groceries so others can socially isolate,” a compact characterization of the implicit risk-bearing contract that many face-to-face workers are taking.5 It is entirely possible that most face-to-face workers regard such risk-bearing as unproblematic because they are grateful to have a job, because they consider themselves fairly compensated for risk-bearing, or because they treat risk-bearing as a matter of honor, duty, or responsibility (much like going to war for one’s country). It is also possible, however, that they harbor some resentment toward remote workers or their employers for failing to fully share in the new risks that the crisis has brought on.

The latter resentment-stressing formulation has received considerable play to this point. The journalist Alastair Sharp featured, for example, a food-delivery worker who resented delivering “junk food, cheesecake, and bubble tea to rich people in high-rise condos.”6 In a New York Times opinion piece, Steven Greenhouse emphasized that this resentment is often directed toward remote workers and employers, with face-to-face workers seeing themselves as “risking their lives while chief executives earn millions and … highly paid white-collar employees are working safely at home.”7 As Greenhouse further argues, face-to-face workers are “furious that their employers are not doing enough to protect them against the pandemic,” and they are also “angry that … they haven’t given them raises or hazard pay” to compensate for the extra risk.8 This account comports well with the recent wave of strikes, walkouts, sickouts, and related protests by food shoppers, warehouse workers, bus drivers, poultry and meatpacking workers, and painters and construction workers.9

The preceding line of commentary adopts, if only implicitly, the concept of a “noxious contract” in which a power asymmetry obliges workers to accept working conditions that entail considerable risks. The literature on noxious markets suggests that contracts of this sort are more likely to generate resentment when risk-bearing workers (a) are at risk of substantial harm, (b) are facing new or poorly understood risks, (c) are drawn disproportionately from disadvantaged racial or ethnic groups, (d) can directly identify the beneficiary of their decision to bear risk (e.g., recipients of home deliveries), (e) are assuming risk on behalf of unimportant objectives, (f) are partly coerced into the contract (typically because of a shortage of jobs), (g) enter into a contract that’s exclusively about risk-bearing and shorn of complicating features that might otherwise obscure the risk-bearing portion of the contract, or (h) are not working in an organization or society that stresses the importance of collectively shared duties and responsibilities (e.g., wartime societies).10 Although there have long been noxious contracts that bring together various resentment-generating conditions, the current crisis has increased the number of jobs in which some of these conditions are present (e.g., an increase in the risks associated with face-to-face interaction) and may have also increased the salience of many of them (e.g., an increased capacity to directly identify the beneficiaries of risk-bearing).

It is unclear whether many face-to-face workers understand their contracts as truly noxious in this sense. Because face-to-face workers face varying levels of risk and satisfy other resentment-generating conditions to varying degrees, it is especially difficult to anticipate whether many will feel resentful or exploited by those who are not bearing comparable risk. We may find, for example, that resentment only surfaces when the risk-bearer enters into a direct risk-transfer contract with a known beneficiary (e.g., delivering food to someone’s home). It is also possible, however, that face-to-face workers will express their resentment in a quite general class-wide form because they view all remote workers as “running away from risk,” selfishly protecting only themselves and their families, and thus violating the crisis trope that “we’re all in this together.”

We have focused to this point on resentments that arise when health risks are differentially shared. The second type of worry in play, again laid out by several well-known journalists, features the resentments that may also arise when economic risks are differentially shared. In a New York Times commentary, Bret Stephens points out that remote workers are largely protected from economic risks, whereas workers in many face-to-face settings (e.g., restaurants, brick-and-mortar stores) are more likely to be laid off or shifted over to part-time work.11 The new economy is, for Bret Stephens, increasingly built around the very different economic risks that these two classes face: “For the Remote, an image on the news of cars forming long lines at food banks is disconcerting. For the Exposed, that image is—or may very soon be—the rear bumper in front of you.” This account stresses that face-to-face workers face two new risks, not just the health risks that come from working in dense face-to-face settings, but also the precariousness of working in a sector that is especially vulnerable to mandated closures and pandemic-induced declines in demand. The remote class, by contrast, remains safely at home and (largely) protected from both types of risk.12

The “buying safety” story

The foregoing accounts involve conflicts between groups that occupy different positions in the class structure (as laid out in Figure 1). We have suggested that face-to-face workers (a) may resent remote workers for failing to shoulder their fair share of health risks, (b) may resent employers for failing to protect them from health risks, and (c) may resent employers, managers, or government officials for failing to protect them from the economic risks to which they are especially subject (because shelter-in-place orders, restaurant closings, and other pandemic responses disproportionately affect them). Although many journalists have suggested that such inter-class conflicts could intensify during the crisis, others have instead implied that the most important antagonisms aren’t narrowly class-based but instead pit those who have the money to buy protection from risk against those who don’t. This second stream of commentary, to which we now turn, focuses on abstract challenges to the legitimacy of using one’s income or wealth to buy protection.

This simpler “buying safety” story was featured, for example, in a host of reports about well-off residents of New York City deciding to retreat to safer outlying communities, initially just for short stays but more recently as purchasers of new estates.13 These early stories emphasized the hostilities that were engendered when newcomers exposed locals to infection, emptied out grocery shelves to stock their freezers for a year, and otherwise used their money to protect themselves.14 The view that it’s unseemly to buy safety surfaced again when the billionaire David Geffen posted on Instagram that he’s “isolating in the Grenadines” on one of the world’s largest private yachts.15 The response from the public was again a stinging repudiation of those who fail to appreciate that only the one percent can afford protection of that caliber.16

In a society that’s always allowed extra life expectancy to be purchased (via higher-quality health care, better living conditions, and much more), it might seem strange that “buying safety” is suddenly called into question. Although the life-for-money exchange is indeed as old as market economies themselves,17 a pandemic may allow us to see it afresh in a balder form that induces people to reconsider its legitimacy. If crises are viewed, for example, as moments in which we’re supposed to come together, the use of private resources for private protection may come off as especially unseemly.

The ongoing discussion of “buying safety” has in fact been taken up in two quite distinct ways. As we have emphasized, there is a large body of commentary emphasizing the resentment that over-the-top purchases of safety might engender, but there’s also a secondary line of commentary suggesting that, insofar as there is any resentment at all, it is likely intermixed with a large dollop of envy. When someone is envious, they are typically (a) “looking up” toward a class that is higher than their own, and (b) wanting to partake in the experiences, lifestyle, or consumption opportunities associated with that higher class.18 This tendency to “gaze upward,” which has been well studied,19 may become more pronounced when those at the top are straightforwardly buying life itself. In a recent New York Times article, Nancy Wartik indeed suggests that this upward gaze is becoming more common, not just because selling life itself is especially troubling but also because we’ve become more aware of differentials in the capacity to buy it:20

Growing wealth disparity, along with ubiquitous social media, appears to have made us all less satisfied (and snarkier). The pandemic has fueled the fire. Essential workers envy those working at home. People who were laid off envy those who weren’t. Those home-schooling young children envy those who aren’t. We all envy the rich.

This line of reasoning suggests that we should examine our data carefully for evidence of envy as well as anger or resentment. It is an important distinction because envy, unlike resentment, does not call into question the legitimacy of inequality itself. When one feels envious, it typically entails a wish to improve one’s own circumstances, but not necessarily a wish to eliminate the inequality that provoked the feeling of envy. In this sense, envy is not a radicalizing emotion, whereas anger, hostility, and related types of resentment might be.

The new class structure

Before presenting any evidence on resentment, envy, and other sentiments, it is useful to first examine the new health and economic “risk divides” that stand behind any possible changes in sentiment. We pay particular attention to trends in the size and composition of the three main classes in Figure 1 (i.e., face-to-face workers, remote workers, and the precariat).21

We thus begin by estimating the percentage of workers who worked remotely in February, May, and August of 2020 (see Figure 2). These three months were chosen to represent (a) the pre-crisis baseline (February), (b) the turn to shelter-in-place and related forms of social distancing (May), and (c) the first “reopening” of the economy (August). Because a consistent measure of remote work is not available for this full period, we have combined information on pre-crisis remote work from the American Community Survey (ACS), demographic and work information for our period of interest from the Current Population Survey (CPS), and information on remote work during the crisis from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).22 The latter information refers to employed persons who “teleworked or worked at home for pay at any time in the last four weeks because of the coronavirus pandemic.” This measure of crisis-induced remote work, when combined with an imputation based on ACS and CPS data of remote work arranged for reasons unrelated to the crisis, allows us to estimate trends in the total percentage of workers who are working remotely by gender, racial, and ethnic group.23

The results from this analysis, as presented in Figure 2, make it clear that remote workers remained a very large sector of the labor force even after the summer reopening. Between May and August, the overall number of remote workers declined by only 11.3 percentage points (from 41.4% to 30.1% of the workforce), a result that is consistent with widespread reports that many firms have been satisfied with remote-work productivity and are discouraging workers from returning to brick-and-mortar offices.24 The second key conclusion from Figure 2 is that remote work—and the protection from health risks it affords—is very unequally distributed. By May of 2020, the percentage of workers who worked remotely differed starkly by gender, race, and ethnicity, with most of the gaps remaining large even as the economy grew in August. The share of women, white, Asian, and non-Hispanic remote workers is consistently higher than that of men, Black, other non-white, and Hispanic workers. The available evidence suggests that such disparities in the availability of remote work are a key source of disparities in health risks.25

The other main risk in play during the recession is of course the risk of losing one’s job or being underemployed.26 These economic risks are also very unequally distributed. In Figure 3, we use the same CPS data to estimate inter-group differences in the size and composition of the precariat, a task that is comparatively easy because we can now rely on well-measured labor force categories (i.e., laid-off, unemployed, underemployed, discouraged).27 We simplify the exposition here by presenting, for each of these labor force categories, the percentage points of growth between February and August of 2020. This timespan suppresses the very extreme disparities at the beginning of the recession and focuses on the more modest (but still large) disparities after the reopening.

The first column of Figure 3 shows that, as a percentage of all working-age youth and adults (aged 16 to 64 years old), the precariat grew by 5.1 percentage points between February and August, a growth driven in large part by the takeoff in the number of laid-off workers. The precariat grew most among women and in Black, Asian, and Hispanic populations. It follows that the very same groups that are disproportionately exposed to health risks (by virtue of crowding and other forms of segregation into face-to-face work) are, for the most part, also disproportionately exposed to work-based precarity.28 Although the Black and Hispanic populations face the “double burden” of economic and health risk, the Asian population combines large increases in remote work (and thus reduced health risks) with large increases in precarity (and thus increased economic risks). The underlying sources of precarity also differ widely by group, with Native American and Hispanic populations facing a larger rise in underemployment and Black, Asian, and “other” populations facing more layoffs.29 These differences, some of which are quite stark, will of course affect how the crisis is experienced and understood.30

The three gazes

Given this quantitative backdrop, we can now turn to our AVP interviews, with the goal of using them to better understand how face-to-face, remote, and other workers are reacting to the new “risk divides.” In Table 1, we provide socioeconomic and demographic information on the 134 respondents used here, all of whom were interviewed in April through August of 2020. These respondents have been drawn from a stratified address-based sample of 54 AVP communities.31 Although these AVP communities represent a wide range of regions and community types, the pooled sample is not representative of the United States as a whole because (a) the AVP communities interviewed during this time period are not a random draw of all U.S. communities, and (b) low-income households within each community were oversampled. The marginals in Table 1 are, for the most part, consistent with this design.32

The AVP sample, while relatively small in size, is an attractive resource because it allows us to characterize sentiments that arise organically in conversations about the pandemic and recession, work relations, recent changes in income or employment, strategies for making ends meet, political views and policy recommendations, and much more. During the interviews, a multitude of opportunities to express “class sentiments” thus emerged, a feature of the AVP that of course differs sharply from forced-response surveys.33 In our analyses of these data, we developed a codebook on employment relations and then trained coders to characterize class sentiments as negative (e.g., angry, exploited, jealous, resentful, guilty), positive (e.g., fortunate, lucky, relieved), or neutral (e.g., indifferent).34 The discussion that follows is based on our initial qualitative work and won’t draw heavily on these formal codes. We have, however, carried out supplementary quantitative analyses of the coded data that accord with the interpretations presented below. In a follow-up to this paper, we will carry out a more formal sentiment analysis that addresses quantitative differences in sentiments by race, ethnicity, and gender.

The balance of our report describes how our AVP respondents understood workplace risks, unequal risk sharing, and related workplace attitudes. The analyses suggest that, contrary to the “class-conflict” or “buying safety” accounts, relatively few AVP respondents were resentful or envious of other classes, that they only rarely “looked upward” at those more fortunate, and that they were more likely to fix their gaze elsewhere in ways that didn’t bring on invidious comparison. We will show that some people “compare downward” by drawing attention to their privilege relative to those less fortunate, that others “look outward” towards the larger community in recognition that times of crisis require banding together with good grace and good will, and that yet others “look inward” as they cope with reductions in work hours and other employment challenges by drawing on self-protective strategies.

We review each of these three gazes—downward, outward, and inward—in turn. In the presentation that follows, we will distill a complicated set of responses into these three archetypes, recognizing that all classifications of this sort are necessarily simplifications. We offer up this particular characterization of class sentiments as a hypothesis that may need to be qualified as further analyses are carried out and as class sentiments change and evolve over time.

The compassionate downward gaze

The “downward gaze,” which entails drawing attention to one’s privilege, is a useful starting place because it was so frequently in evidence among our AVP respondents. The way in which our respondents defined privilege was quite variable, but many felt it was incumbent on them to identify some type of privilege and recognize it. The common theme was that—during a crisis—it is one’s duty to recognize the pain of those less fortunate. When people found themselves complaining about their own personal struggles, they tended to quickly catch themselves, issuing the requisite corrective to reassure that they’re not tone-deaf and that they well appreciate that others have it worse.

This sentiment emerged frequently among those who were able to convert to working remotely during the crisis and thus maintain their income. In one of our interviews, a white pharmaceutical professional found himself rehearsing the many advantages of working from home, such as being able to put in 18-hour days because of the time saved by not having to commute. After concluding it’s “actually a better way of working,” he then caught himself and emphasized that, although it’s working out well for him, he appreciates that he’s lucky and that others are struggling:

I think I’m just exceptionally fortunate that I’m doing the type of job that I’m doing, that I can take it home. I feel for the people that can’t do that.

The same “catching oneself” dynamic played out for a multiracial remote worker who found herself waxing poetic about her fancy new home office, with “a pretty good-sized desk” and “dual monitors,” but then quickly recognized that it’s her obligation, given all that’s going on, to feel grateful for “things that are going well.” When our interviewer later asked her “what life has been like for you over the past year,” she initially effused but quickly acknowledged the complicated context:

In general, I’ve been feeling pretty great. I feel like—barring the whole pandemic and the world just turning into a dumpster fire—things have been going pretty well.

Likewise, when another remote worker found herself fretting that the pandemic might delay her wedding, she quickly caught herself and expressed guilt for “stressing about this when people actually have real problems.”

For other people, the feeling of privilege didn’t take the form of a guilty afterthought, but was much closer to a front-and-center sensibility. When a white adjunct professor was asked, for example, to discuss her experiences as a remote worker during the crisis, she immediately responded with the disclaimer, “I'm definitely speaking from a position of privilege here.” After establishing that point, only then did she allow herself to complain, noting that “I hate, hate, hate teaching online, but I managed.” When the conversation next turned to the criminal justice system, she allowed that “no one in my immediate circles has been arrested,” stressing that this is again a “function of my own racial privilege.” In discussing her husband’s situation, she likewise stressed from the start that, even though it’s not a “super-exciting job,” it’s at least “a stable job and he can work from home, which we’re thankful for” (white woman, age 37, remote worker, professor).

Although a professor is perhaps especially adept at what might be called “privilege talk,” the concept of racial and economic privilege was in fact frequently raised in our interviews, with one person referring to her access to amenities that are “dripping with white privilege,” another suggesting that his ability to self-protect from “all this COVID stuff” is a “function of my privilege,” and many others making similar references to the protective effects of their privilege. As these comments make clear, some of the references to “privilege” called out white privilege in particular, thus suggesting that this new “privilege talk” may stem as much from ongoing discussions of systemic racism as the class-based inequalities that the current crisis has also revealed (see our forthcoming report on policing and protests for more details). In other cases, “privilege” was used more ambiguously, and it was unclear whether it referred to class-based privilege, racial or ethnic privilege, or the intersection between the two. Because there are profound racial and ethnic disparities in class membership (as Figures 2 and 3 reveal), this distinction is hardly an easy one to make in everyday conversation, hence it’s perhaps unsurprising that it was often skirted.

The foregoing conversations feature remote workers who, because they’re faring reasonably well, perhaps found it natural to emphasize their privilege. What about remote workers who faced more difficulties? We found that they too worked hard to turn the discussion to those who were less fortunate than them. To be sure, they did discuss their own problems, but typically they didn’t allow themselves to complain for too long before likewise catching themselves and recognizing that remote workers were less vulnerable to layoffs or reductions in hours. When a white programmer confessed that she was “stressing over money” and, in particular, worrying that her children had precarious employment situations and may need her help, she then calmed herself by rehearsing the “one day at a time” refrain and turning her gaze downward:

I mean, we’re fortunate me and my husband both still have jobs and as far as I know we’ll have them into the foreseeable future. Not everybody has got that.

This “downward gaze” was also in evidence for remote workers who faced yet more fundamental worries. For example, a Black salesperson experiencing a dramatic falloff in sales and income allowed himself a lead-off sentence of despair, a sentence that was clipped short and followed up immediately with a longer acknowledgement of all those suffering even more than himself:

It's been a slow, slow hell quite honestly. I mean, I'm not going to take away from people who have health issues and it's probably worse for people who've actually caught the virus.... You know, I'm still blessed to have a roof over my head and be able to put food on the table for me and my pets, but I would just say it definitely hit pretty hard financially.

This is all to suggest that, no matter how overwhelming their problems, remote workers tended to compare downward to those who were suffering yet more. Although the media has taken many celebrities to task for their insensitivity to those who are less fortunate, our interviews suggest that the country’s rank-and-file remote workers are, for the most part, quite cognizant of the suffering around them.

We have so far shown that remote workers, even those facing serious problems, were at pains to compare themselves to those suffering more than them. It might be thought that, by contrast, face-to-face workers will be less likely to gaze downward: The “noxious contract” hypothesis has it that, because face-to-face workers are assuming risks on behalf of uncaring employers and remote workers, they are more likely to feel resentful than compassionate. We again find little support for this hypothesis. To the contrary, we find that face-to-face workers are responding similarly to remote workers, again adopting a downward gaze toward those less fortunate and with real appreciation for their advantages. This sensibility is revealed, for example, in a white machinist’s effusive gratitude toward a boss who could have laid him off:

I was fortunate to be able to continue working at my present job because we made some parts that were essential, so thank goodness, I did not have to go on unemployment, I didn't have to worry about all that.... I'm thankful I don't have any problems, no money issues, no worries, I'm not going to lose anything. So, in that regard, I was very blessed. I'm very, very thankful, it could have been much worse. My boss could have laid me off, thankfully, he didn't.

Likewise, when a Hispanic stay-at-home mom was asked how she’s faring, she noted that “thank God my husband’s job is essential,” and then immediately turned her attention to others in her neighborhood who are homeless:

Now there are many people in the streets, compared to the amount that used to live in the streets before. You can even see partners with their little kids out there, which is really worrisome, because even though we don't find ourselves in that same situation, I still tell my husband how sad it is seeing so many people in the street.

Although gratefulness and compassion were the dominant reaction, some face-to-face workers did of course express worries about the health risks they were bearing, yet notably these worries did not translate into resentment toward remote workers. When discussing her pharmacy job, a 64-year-old white clerk complained that shoppers rarely wore masks and were coming just to buy “beer and stuff,” hardly the essential trips that they should have been making. It’s clear that she felt resentful, but her antipathy was directed downward toward the “low socioeconomic status” shoppers who frequented the pharmacy, certainly not upward toward remote workers laboring in relative safety.

The outward gaze

With the “downward gaze,” workers are coping by (a) finding a reference group that is faring worse than they are, and (b) reminding themselves that, relative to this group, they have no reason to complain. In some cases, we observed that a somewhat different coping strategy was in play, one in which the gaze turned outward rather than downward. When a worker gazes outward, they are not focusing on the problems of those who have been hardest hit, but instead on the problems that everyone is facing during the crisis (such as worries about the rising death toll or worries about when a vaccine will become widely available). The outward gaze is encouraged by the many advertisements, billboards, and public pronouncements to the effect that “we’re all in this together.”

Although the outward gaze was less frequently adopted (among the three “gazes” we identified), it nonetheless surfaced with surprising frequency, especially among low-income groups and racial or ethnic minorities. It would be easy for face-to-face workers and Black, Hispanic, and Native Nations populations to be cynical about collective pronouncements to the effect that “we’re in this together” given that they are disproportionately bearing the risks of face-to-face work (see Figure 2). We observed, however, a striking proclivity for outward-looking compassion despite such inequality in risk-bearing, a proclivity that is consistent with other evidence suggesting that less privileged groups display a more collective orientation.35

The outward gaze often takes the same “catching oneself” form that emerges with the downward gaze. In the midst of discussing their problems, our interviewees seemed to recognize that they might be coming off as self-centered, with their corrective now taking the form of clarifying that they appreciate that everyone has problems during a crisis and that their own problems are unlikely to be unique. This led them to stress, for example, that “everybody’s in the same boat really,” that “it’s hard for everyone,” or that “an emergency’s happening and we just gotta get through [it].” In some cases, the term “everybody” really meant “everybody I know,” a sleight that concealed the extent to which one’s networks are hardly a random draw and may therefore create the impression of more widely shared risks than is indeed the case. This tendency to generalize on the basis of personal networks may explain why our interviewees were so quick to assume that others were experiencing as many challenges and difficulties as they were.

Although the outward gaze typically took the relatively limited form of conversational self-scolding, it also expressed itself in acts of sacrifice and giving. In some cases, the acts were comparatively small, like a teacher who focused on helping her students by “walk[ing] them through an emergency while trying not to panic about my own life.” But some of our interviewees made more substantial sacrifices. When a young Black essential worker learned that his employer was struggling and had to make cuts, he immediately volunteered to reduce his own hours because “you have [other] people who are feeding their families with this money.” These acts of sacrifice sometimes came from workers who were facing substantial risks of their own and were not especially well off (see our forthcoming report on material hardship for a related discussion).

The inward gaze

Given the depth of the recession, many people found it difficult to adopt this compassionate “outward gaze,” as their own problems were simply too overwhelming. When jobs are lost and bills are mounting, it is natural to turn inward and focus on one’s own problems, with all available bandwidth being drawn upon. This inward turn, which was common among those who were laid off or dealing with reduced hours, leaves less energy for compassion or for feeling resentful of those responsible for one’s problems. Although the inward and outward gazes entail very different responses to the crisis, neither works on behalf of the high-conflict outcome that some media commentators had anticipated.

These inward-looking accounts are distressing to hear because the sense of anxiety and worry is often palpable. For many people, all thought and energy is initially devoted to finding work, but as savings are exhausted attention then turns to deciding which bills to pay and to dealing with rising debts. When a Hispanic factory worker was asked how he’s been faring since the virus hit, his response revealed this overwhelming worry about hours being cut and bills going unpaid:

Man, it's killing me; man, it's killing me. Bills are piling up, and we only working four days a week, they put us at a limit, so we can't collect more work.... It's killing us, yes the food stamps are helping us, but that don’t pay the bills. I got a car loan that’s almost 500, my rent is almost 700, like how am I supposed to do all that, how do you ... limit me to a certain amount of hours?

At a later point in the conversation, the interviewer asked him how he has been handling the stress, and again the overwhelming anxiety came tumbling out:

The bills ain’t going to get paid by themselves. And that’s not my wife’s fault, I'm the man of the house, I got to do it.... It's tough, I got to put on—how do you say this—a facade, like I got to be strong, I can't show them what I feel, even though the baby don't know, but wife knows, how do I go to sleep, I got to fake it, I got to fake everything.

In this case, the first-order problems of finding work and dealing with bills led to so much anxiety that it became its own problem, interfering with sleep and reducing bandwidth. These first-order problems didn’t lead to outward conflicts with his family members, coworkers, or employer but instead were internalized (i.e., the “inward gaze”) at real cost to his physical and emotional well-being.

Across the country, our interviews reveal people being pushed to their limits in this way, not typically reaching a breaking point but perhaps getting close. Even when they are ultimately able to return to their jobs or to find new ones, they are often consumed with worry about the debts incurred in the interim. As a Hispanic nursing assistant put it, she’s simply “suffocating” in debt because her minimum-wage hours were cut, ultimately motivating her to find a new job that could offer more hours. When asked to describe her life at her new job, her simple assessment—that it’s been “hell”—turned on her ongoing worries about bills:

I'm three weeks in at my new job, and it’s like I'm trying to get back on my feet, and I have so much things that ... I have to catch up on, that I feel like: ‘When am I going to get a piece of air?’ Because it’s like I'm suffocating in bills and debt.... So, yeah, since Corona, I can say it literally has been hell.

Although her words are thick with anxiety here, at a later point in the interview she recovers and expresses some optimism, emphasizing that she realizes that “things take time” and “nothing happens overnight.” The key point here is that she sought to console herself with such tropes (i.e., the “inward gaze”) rather than expressing any outward-looking resentment, blaming others, or pointing to systemic inequalities in risks.

The most worrying cases are of course those in which hope has been utterly lost. For some of our respondents, the inner resources for coping seem to have been fully tapped, and the tension and anxiety become all-consuming and convert to a wider paralysis. After being laid off from his warehouse job, a Hispanic man discussed how he is at a loss and unable to get anything done:

It's been pretty hard. I can't get a job, really. Can't really do anything.... It's just, for me personally, it's a nightmare. Really, a nightmare. I can't really get anything accomplished. So, yeah. Just, everything in a nutshell is a nightmare.

In other cases, our interviewees were so distressed that they could not gather themselves to respond to our lead prompt to “tell the story of their life,” a prompt that is supposed to trigger a conversation about the larger arc of one’s life. When an unemployed Hispanic worker faced this prompt, he found it impossible to start at the beginning, instead he had to turn immediately to his current difficulties finding a job and his full-on distress as his life was becoming ever more chaotic:

In February I was dropped, the company closed down because of financial problems, it was not able to meet its contracts. And it has not been easy. These months have not been easy. Because I have looked for work, but I couldn’t find it.... You have to spend the 24 hours of the day with the mortification that every weekend there are debts to pay, that you are not being useful .... The routine is bad. I’m at an impasse.

As the interview unfolded, he referred repeatedly to being “stalled,” to his “isolation,” to the lack of a “routine,” and to his “anguish.” In this case, our interviewer ultimately brought him back to less distressing topics (and referred him to local resources for help), but it is clear that he was being taxed beyond his limits.

The simple conclusion here: There is little time for the luxury of looking outward when bills are unpaid, work cannot be found, and the world is pressing in. The above quotes also reveal that this “inward gaze,” as we have labelled it, is disproportionately the burden of Hispanic and Black people. Because the recession has hit them harder, and because their financial reserves are lower, it is hardly surprising that they have faced the most duress and stress (see the Material Deprivation report for details).36

Looking to the future

We led with the hypothesis that a new class structure has emerged around a noxious contract that obliges those with less power (e.g., face-to-face workers) to accept extra risks. The rapid spread of noxious contracts might well increase conflict between (a) employers and the face-to-face workers who are being asked to accept high-risk contracts, and (b) remote workers and the face-to-face workers who are bearing risk on their behalf. Although there is a long history of noxious contracts, the “crisis variant” of the noxious contract may be especially conflict-generating because it pertains to risks that are new and poorly understood, because it is inconsistent with the sentiment that “we’re all in this together,” and because the new risks are disproportionately imposed on disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups (possibly to an even greater extent than has been the case with other long-standing risks).

Using the AVP data and other sources, we have presented analyses that do not comport with these accounts, as plausible as they might seem. Because the AVP sample is small, and because the crisis is rapidly evolving, we should stress that our interpretations are far from definitive. It is nonetheless notable that the AVP data aren’t revealing any decisive ramp-up in workplace conflict.

We have shown, to the contrary, that most workers are focusing on other types of comparisons. We observed that many people “compare downward” by emphasizing their privilege relative to those less fortunate, that others “look outward” in recognition that times of crisis require banding together, and that yet others “look inward” as they cope with unusually stressful challenges. Although many ways of coping are therefore in play, none of them entail invidious comparisons that then lead to resentment or conflict.

We are certainly not suggesting that inter-group tensions and conflict were nowhere to be found in the AVP data. Throughout our interviews, there was in fact much discussion of racism, protest, and racial conflict (see the Race and Protest report for details), but that discussion was not typically framed in terms of noxious contracts or otherwise refracted through a class-conflict lens. There was also much evidence of political partisanship in the form of resentment, hostility, or anger directed to those with different political views. These results are consistent with the long history in the United States of successfully suppressing inter-class conflict while elevating other forms of conflict.

What types of class sentiment did emerge? Instead of resentment or envy, the dominant sentiments were those of fortitude and stoicism, a sensibility that might stem from the view that the real enemy is from without (i.e., a virus) rather than from within (i.e., another social class). In a now-famous interview, President Obama referred to the U.S. as a great country that had “gotten a little soft,”37 a controversial characterization that nonetheless resonated with some commentators.38 Although our interviews reveal a country that’s anything but soft, it bears noting that such fortitude and stoicism also undermine the class-based interpretations of the current crisis that some commentators anticipated.

This is not to suggest, of course, that this collectivist sensibility will necessarily persist as the crisis stretches on. The resilience and resolve that we’re seeing to date is striking, but large swaths of the population are facing such extraordinary challenges that it may become impossible to continue to project strength over the very long haul. Because the pain is being borne so unequally, there may well come a time when protestations to the effect that “we’re in this together” ring hollow, and less individualistic and more structural interpretations of the crisis prove more attractive.

David Grusky is Edward Ames Edmonds Professor in the Humanities and Sciences, Professor of Sociology, and Director of the Center on Poverty and Inequality at Stanford University. Ann Carpenter is an assistant vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Erin Graves is a senior policy analyst at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Anna Kallschmidt is a research manager at the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality. Pablo Mitnik is an associate researcher at the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality. Bethany Nichols is a graduate student in sociology at Stanford University. C. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University.

Notes

1. Seppala, Emma. 2012. “How the stress of disaster brings people together.” Scientific American; International Crisis Group. 2020. “Covid-19 and conflict: Seven trends to watch.”; Concha, Joe. 2020. “Thomas Friedman to CNN: US potentially heading to ‘second civil war.’” The Hill; Pitts Jr., Leonard. 2020. “In normal times, we’d unite against coronavirus. These aren’t normal times.” Miami Herald.

2. Hamilton, Darrick, Algernon Austin, and William Darity Jr. 2011. “Whiter jobs, higher wages: Occupational segregation and the lower wages of black men.” Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper 268.

3. Hacker, Jacob. 2019. The Great Risk Shift: The New Economic Insecurity and the Decline of the American Dream. New York: Oxford University Press, 2nd ed; Faberman, R. Jason and Daniel Hartley. 2020. “The Relationship between Race, Type of Work, and Covid-19 Infection Rates.” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Working Paper 2020-18.

4. This report is one of an ongoing series of “crisis reports” that use the AVP—as a complement to survey research and qualitative journalism—to report on everyday life in the United States during the crisis. These reports focus on such topics as deprivation and hardship, health and mental health, schooling and childcare, the election and politics, and protest and racism.

5. Ward, Lareign. 2020. “I’m an Instacart shopper. I buy groceries so others can socially isolate.” Vox.

6. Sharp, Alastair. 2020. “Bike couriers in Toronto risking illness to deliver ‘junk food to rich people.’” Canada’s National Observer.

7. Greenhouse, Steven. 2020. “Is your grocery delivery worth a worker’s life?” New York Times.

8. See also Chan, Wilfred. 2020. “Food delivery workers are coronavirus first responders.” NBC.

9. Covert, Bryce. 2020. “The coronavirus strike wave could shift power to workers – for good.” The Nation; McNicholas, Celine and Margaret Poydock. 2020. “Workers are striking during the coronavirus.” Economic Policy Institute; Treisman, Rachel. 2020. “Essential workers hold walkouts and protests in national ‘strike for Black lives.’” National Public Radio.

10. See, e.g., Satz, Debra. 2010. Why some things should not be for sale: The moral limits of markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press; also see Satz, Debra. 2015. “The moral limits of markets: The case of human kidneys”. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 108(1_pt_3), 269–288.

11. Stephens, Bret. 2020. “In this election, it’s the remote against the exposed.” New York Times.

12. The “double risk” to which face-to-face workers have been subjected during the crisis was well expressed by President Biden: “Millions of people putting their lives at risk are the very people now at risk of losing their jobs: police officers, firefighters, all first responders, nurses, educators.” See Tankersley, Jim, and Michael Crowley. 2021. “Biden Outlines $1.9 Trillion Spending Package to Combat Virus and Downturn.” New York Times.

13. Tully, Tracey, and Stacey Stowe. 2020. “The wealthy flee coronavirus. Vacation towns respond: Stay away.” New York Times.

14. Ibid.

15. Luscombe, Richard. 2020. “Billionaire David Geffen criticized for tone-deaf self-isolation post.” Guardian.

16. Stupples, Benjamin and Kevin Varley. 2020. “Geffen’s superyacht isolation draws outrage while industry sinks.” Bloomberg.

17. Chetty, Raj, Michael Stepner, Sarah Abraham, Shelby Lin, Benjamin Scuderi, Nicholas Turner, Augustin Bergeron, and David Cutler. “The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014.” Journal of the American Medical Association 315(16), 1750–1766.

18. For a good discussion of envy, see the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2016. “Envy.”

19. See, e.g., Robert H. Frank. 2007. Falling behind: How rising inequality harms the middle class. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

20. Wartik, Nancy. 2020. “Quarantine envy got you down? You’re not alone.” New York Times.

21. The stylized representation of the class structure in Figure 1 does not comport perfectly with the analyses presented here. The main inconsistencies are that our analyses of remote work in Figure 2 include not only the working class defined in Figure 1 but also (a) self-employed workers (who may or may not be working remotely), and (b) underemployed workers (who show up as members of the precariat in Figure 1).

22. The data presented here pertain to the civilian population ages 16-64. We use ACS data for 2018 (see Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, Erin Meyer, Jose Pacas, and Matthew Sobek. 2020. IPUMS USA: Version 10.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V10.0), and we use CPS data for 2020 (see Sarah Flood, Miriam King, Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles, and J. Robert Warren. 2020. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 8.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V8.0). We have also used tabular data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics on the effects of the pandemic on the labor market in May and August of 2020 (see “Table 1. Employed persons who teleworked or worked at home for pay at any time in the last 4 weeks because of the coronavirus pandemic by selected characteristics,” May and August 2020, accessed October 10, 2020).

23. The ACS includes an item about methods of transportation to work that includes “worked at home” as one of the possible responses. Although not intended as a measure of remote work, this item is nonetheless frequently used to estimate the share of people who worked from home in normal (i.e., pre-pandemic) times. We estimated predictive models of “worked at home” using machine learning with cross-validation to compare approaches (with one-third of the ACS sample held out for out-of-sample prediction). The best such model used Lasso logistic regression with the tuning or shrinkage parameter selected by ten-fold cross-validation. This model and the CPS data for February, May, and August were then used to estimate the share of people working from home not due to the pandemic (both overall and by gender, race, and ethnicity). These estimates, when combined with BLS data on people working from home due to the pandemic, allowed us to estimate the total number of people working from home in May and August.

24. Friedman, Gillian, and Kellen Browning. 2020. “July is the New January: More Companies Delay Return to the Office.” New York Times.

25. Chang, Serina, Emma Pierson, Pang Wei Koh, Jaline Gerardin, Beth Redbird, David Grusky, Jure Leskovec. 2020. “Mobility network models of COVID-19 explain inequities and inform reopening.” Nature 589, 82–87.

26. The CARES act reduced the risk associated with unemployment, but it did not of course eliminate all risk (because benefits may be less than earnings while employed, because they may be exhausted before a new job is found, and because some people do not qualify for unemployment insurance).

27. The labor force concepts in Figure 3 are those used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). These concepts are defined as follows: “underemployed workers” are people employed part time because of slack work, unfavorable business conditions, inability to find full-time work, or seasonal declines in demand; “unemployed workers” are people who are jobless, available to work, and have looked for a job in the last four weeks or are in temporary layoff; “laid-off workers” are unemployed workers who expect to be recalled to work within 6 months; and “discouraged workers” are people who currently want a job and are available for work, have looked for work in the last 12 months (or since they last worked if they worked within the last 12 months), but have not looked for a job in the last four weeks for reasons indicating they don’t believe they would be able to find one if they did. The categories are constructed to be mutually exclusive (e.g., the “unemployed” category excludes those who are laid off).

28. This is obviously not to suggest that the only source of health disparities is the segregative processes that crowd Black, Hispanic, and other workers into face-to-face occupations. These disparities also arise from a host of other systemic and institutional causes (e.g., differential access to health care). For an insightful discussion of occupational crowding, see Barbara Bergmann’s influential introduction to the concept Bergmann, Barbara R. 1971. “The effect of white incomes on discrimination in employment.” Journal of Political Economy 79(2), 294–313.

29. For Native Americans, the “discouraged worker” category declined between February and March by 0.2 percentage points, a decline that we have rounded to 0.0 for ease of presentation.

30. There is a large literature exposing the many inequalities that the crisis has engendered. See Long, Heather, Andrew Van Dam, Alyssa Flowers, and Leslie Shapiro. 2020. “The Covid-19 recession is the most unequal in modern U.S. history.” Washington Post.

31. To protect the confidentiality of our respondents, the names of the communities in the AVP sample are not released.

32. During this time period, childcare responsibilities made it difficult for many women to participate in a long immersive interview, thus reducing their response rates.

33. The AVP protocol uses normative anchors to address the contaminating effects of presumptions (on the part of the respondent) about what types of responses are either socially desirable or preferred by the interviewer. Because the protocol makes direct reference to the wide range of positions that different people hold, it signals to respondents that we’re non-judgemental, that all positions are acceptable, and that this is a safe space to openly share their views.

34. We followed standard procedures for the analysis of qualitative interview data. See, e.g., Kathleen Gerson and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing. New York: Oxford University Press.

35. See Rucker, Derek D., Adam D. Galinsky, and Joe C. Magee. 2018. “The Agentic-Communal Model of Advantage and Disadvantage: How Inequality Produces Similarities in the Psychology of Power, Social Class, Gender, and Race.” Advances in Experimental Psychology 58, 71–125.

36. When stress is measured with the AVP’s survey items, very large racial and ethnic differences emerge. In a supplementary quantitative analysis of the coded interviews, we likewise found that community-level concerns surfaced frequently in our conversations, especially among Black interviewees. Also see Brannon, Tiffany N., Hazel Rose Markus, and Valerie Jones Taylor. 2015. “’Two Souls, Two Thoughts,’ Two Self-Schemas: Double Consciousness Can Have Positive Academic Consequences for African Americans.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 108(4), 586–609.

37. Shapiro, Ari. 2011. “Obama learns ‘lazy’ is a four-letter word.” National Public Radio.

38. Hruby, Patrick. 2011. “Red, white, and goo: Has America gone soft?” Washington Times.

The American Voices Project gratefully acknowledges support from the Annie E. Casey Foundation; the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the Center for Research on Child Wellbeing at Princeton University; the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative; the David and Lucile Packard Foundation; the Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta, Boston, Cleveland, Dallas, New York, Philadelphia, Richmond, and San Francisco; the Ford Foundation; The James Irvine Foundation; the JPB Foundation; the National Science Foundation; the Pritzker Family Foundation; and the Russell Sage Foundation. The Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality is a program of the Institute for Research in the Social Sciences.

The authors thank Cocoa Costales, Tony Davis, Ben Horowitz, Susan Longworth, Kimberly Payne, Alex Ruder, Theresa Singleton, and Julie Siwicki for their helpful comments. The views expressed here are the authors’ and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Federal Reserve System, Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, or the organizations that supported this research. Any remaining errors are the authors’ responsibility. The American Voices Project extends our sincere gratitude to everyone who shared their story with us. We would also like to thank our researchers and staff.